Another family moves to the streets. They tell me their rent was increased by $500 a month. A disheveled lady who may have been in her sixties shares that she was recently divorced and moved into her car but she couldn’t afford to register it and the police confiscated her vehicle that week. She asks if there is a shelter but of course there is no room for her.

A young couple dragging new suitcases and as yet unsoiled sleeping bags find their place at the end of the food line. The numbers of uncounted grow larger by the day.

A total of 861,664 American families lost their homes to foreclosure in 2008, according to RealtyTrac. But the number of Americans suffering homelessness was 250,000 less than before the crisis according to the numbers collected using the Point in Time count. Something isn’t adding up.

The 2017 report by The National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty, “DON’T COUNT ON IT” reminds its readers that, “It is important to have an accurate estimate of the number of people experiencing homelessness in this country if we want to enact effective laws and policies to address the homeless crisis.”

The report also points to a 2001 study using data collected from administrative records of homeless services providers estimated that the actual number of homeless individuals is 2.5 to 10.2 times greater than those obtained using a point in time count, which translates to an equivalent annual number of 1,374,820 to 5,609,265 homeless individuals in the United States for 2016. The point in time count for 2016 found only about 550,000 people, leaving 800,000 to 5 million homeless people uncounted.

Undercounting helps reduce the urgency to seek solutions. City officials in Santa Cruz, California relied on the undercount to argue before Federal District Judge Edward Davila’s court that they would be providing adequate shelter, justifying their plan to drive several hundred people from a homeless camp in a field behind the Ross Dress for Less Department Store. The city was ultimately only able to provide space for sixty or seventy of those evicted from the safety of the camp. This left hundreds of homeless people to wander the streets of Santa Cruz without a place to go, upsetting many other members of the community. Real numbers do count.

The Santa Cruz Sentinel reported on Aug 5, 2019, “The number of homeless individuals in Santa Cruz County fell nearly 4% from 2017, data from a biennial point-in-time census shows. The snapshot of the county’s homeless population, conducted on a single day in January, found 2,167 homeless individuals compared to 2,249 two years earlier.” The increase in people attending the twice-weekly Food Not Bombs meal who report they just became homeless appears to show otherwise.

The Santa Cruz County Communication Manager made the point, “There is no perfect way to conduct this census (or any other), but I expect we’ll continue to participate given the Count’s important not just for McKinney-Vento funding but as the backbone of state funding now being made available to counties, large cities, and CoCs. Without it, our already limited resources to address this crisis would be diminished further.

” A $20 million grant to Santa Cruz County from the state’s Homelessness Emergency Aid Program in 2019 had little to no impact on providing for those who live outside. The funding was not able to provide the camp operated by the Salvation Army at 1220 River Street showers or fresh drinking water for the 60 souls grateful for a place in a cheap pup tent. An August 2019 Facebook post by the Homeless Service Center announced that they were able to house a family. Hopefully, the center was able to house more people with their share of the $20 million but chose to highlight the most sympathetic victory.

A more accurate accounting of the millions of internally displaced people living outside in the United States might be enough to shock Americans into action demanding that political leaders respond with aggressive affordable housing policies, livable wages and an end to the criminalization and dehumanization of the homeless.

The number of Americans living in poverty before the global economic crash was believed to be over 140 million. Studies report that nearly 40 percent of those living in the United States in 2019 would struggle to pay an unexpected $400 expense. As the economy disintegrates the number of people finding themselves without a home is certain to increase: The 2020 Census of the homeless is likely to be outdated before the numbers are published.

I have spoken with several well-meaning Santa Cruz County employees about the Smart Path to Housing and Health program. Their website describes it “As Santa Cruz County’s coordinated entry system, Smart Path streamlines access to housing assistance and services for all people experiencing homelessness. Individuals and families will complete uniform assessments at a variety of easy to access locations throughout the county.”

People come to me excited that they have completed the Smart Path assessment and are excited that they will be housed soon only to tell me months later that, for one reason or another, their promise of housing had fallen through.

A review of the online questionnaire, The Vulnerability Index – Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool, suggests the people who developed the form consider those without housing to be mentally ill or addicted. There are no questions as to how the applicant became homeless or a suggestion that it was the economic system that is responsible for their condition.

The combination of the insulting questions, the fact that the form requires a computer and access to the internet to be completed (which often requires an appointment with a social worker), or that even after completing the form, you or anyone you know has never been offered housing on completion of the form, it wouldn’t be a surprise that many unhoused people might refuse to participate in the 2020 Census.

There is a reasonable fear among some people that the real purpose of collecting all this information is to assist in the detention of people without physical addresses. This makes it even more difficult to get an accurate count of those who live without housing.

Santa Cruz County introduced a program called Focused Intervention Team in February 2019. The six-member team is comprised of deputies and behavioral health experts. County officials explain, “The program addresses frequent users of public services by identifying serial offenders who are change-averse, with a demonstrated track record of disruptive and criminal behavior in local downtowns and other urban areas.” A 2017 Santa Cruz City Council report claims that half of all police contacts were with people who lived outside at the cost of $11 million.

The Santa Cruz County website states, “Many of these individuals suffer from substance abuse, are experiencing mental health conditions or homelessness. But what they all have in common is a willingness to engage in lawless behavior that places them and others at risk.” Sleeping outside or in a vehicle between 11 pm and 8:30 am, sitting within 14 feet of a building wall or public urination (in a community with limited access to toilets) are considered illegal in Santa Cruz.

Sheriff Jim Hart said, “We need clinicians out there working with law enforcement, both on the substance use disorder side and on the mental health side. These teams will work cooperatively in the unincorporated areas and the four cities, receiving referrals from local law enforcement and clinicians, as well as community members, to do early intervention with people whose behavior is escalating and may become violent.”

At this time the only solution for the people targeted is to place them in jail.

Homeless people can also become “the property” of county governments under a new California law. Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 1045, “Conservatorship: serious mental illness and substance use disorders”, into law on September 27, 2018.

According to the San Francisco Weekly: “Once you’re fully conserved, you lose the right to live alone, choose your doctor, access your bank accounts, own a pet, or communicate with the outside world.” The ACLU calls “conservatorship” the greatest deprivation of civil liberties aside from the death penalty.”

The 2018 law only covers people who live outside in San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego counties but is likely to be expanded to all of California as the number of homeless people increases.

Since mental health services, addiction treatment, and housing is unavailable the only place for people who have been identified for conservatorship to be housed is in the county jail. Once the jail facilities are filled, counties will feel pressure to establish some type of alternative.

California is already working on a solution to the overcrowding of county jails. “We are advocating something that I don’t think anybody has advocated, and that is an obligation for people who are living outside to take shelter,” says Sacramento Mayor Darrel Steinberg, co-chair of the Governor’s Statewide Task Force on Homelessness. He has proposed mandating a “right to shelter” for the state’s growing homeless population, obligating individuals without housing to go into an available shelter.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with saying that living on the streets is not a civil right, that you have to come indoors,” Steinberg said. “How we enforce that, work on that, will be for debate and discussion and a lot of good work ahead.”

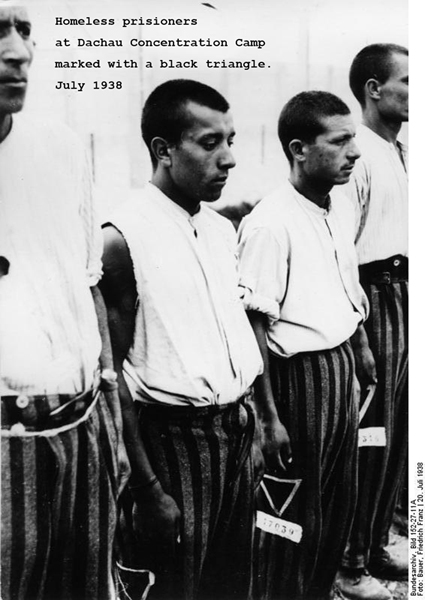

People too poor to afford housing might not want to be counted in the census fearing that they could be forced into a shelter against their will. Many people living outside may also worry that the next step in their obligation to shelter could be that the doors would be locked turning their shelter into a concentration camps.

California is often on the cutting edge: these policies might be adopted by other states. An accurate count of those who live outside during the 2020 census will be challenging in this atmosphere and who could blame those forced to seek shelter in a doorway or park for refusing to cooperate the census.

And if they are not counted in the 2020 Census, how will state and local governments fund programs that do help homeless people, when there are more people becoming homeless every day?