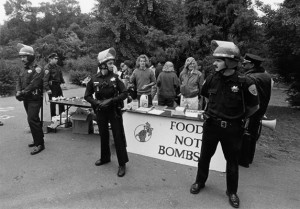

meal in protest to capitalism. March 26, 1981

During the late 1970s, I was active with the Clamshell Alliance and the Coalition for Direct Action and participated in a number of protests at the Seabrook nuclear power station construction site in New Hampshire. Those protests brought the eight of us who started Food Not Bombs together. One of us, Brian Feigenbaum, had been arrested at a protest, and we started to hold bake sales outside the Student Union at Boston University and in public places like Harvard Square to raise money for

his legal defense.

Several of us decided we also needed to build opposition to Seabrook in the Boston area, Boston being the largest city likely to be effected by a nuclear accident at Seabrook. At about the same time, several of our friends discovered that many of the board members of the First National Bank of Boston sat on the boards of the companies building and buying Seabrook Nuclear Power Station.

The bank was using depositors’ money to fund this dangerous project. We decided to start a campaign called the First National Bank Project with the intention of bringing the effort to stop the nuclear station to the people of Boston.

I designed a flyer diagraming the interconnections of the bank’s board members with the nuclear industry. Several on the First National Bank of Boston’s board also sat on the boards of military contractors such as Raytheon as well as on the boards of companies such as Babcock and Wilcox that were profiting from the construction of the nuclear power station. The flyer showed this complex web.

Our first action was outside the Bank of Boston’s headquarters. I was the only one in the group who owned a suit and tie in the group and so was picked to play Bank President Richard Hill in a skit.

The eight founding volunteers of Food Not Bombs met and decided to support the First National Bank Project campaign with food. I recovered boxes of organic produce at my job at Bread and Circus Natural Grocery in Cambridge. We’d previous been collecting such food and delivering all of it to the people living at the projects on Portland Avenue. Following the launch of the First National Bank campaign, we agreed to use some of the food for the campaign.

The second action organized by the First National Bank Project was held outside the annual stockholders meeting of the bank on March 26, 1981. By then, we were calling ourselves Food Not Bombs, and we decided to make a huge pot of soup out of some of the produce I was recovering. We dressed as hobos from the Great Depression era and organized a soup line outside the Federal Reserve Bank at South Station.

As we were preparing the pot of soup, we became concerned that there would not be enough people to finish all the food and that we had also not done enough to draw the number of protesters needed to make the meal resemble a Depression era soup line. We thought of a solution. We’d tell the homeless people at the Pine Street Inn homeless shelter about the lunch time protest. Two of us drove over to the Inn at about midnight. The staff was happy to let us speak to the men. I gave a brief announcement about the purpose of the protest and said that we would be providing a free meal. They were excited more about the protest than the

meal.

The next day Food Not Bombs arrived outside the Federal Reserve Bank dressed as hobos. One of us had a cloth tied up as a bag and filled it with crumpled paper and hung it off a wooden broom stick to look like the bindlestiff one would see in movies from the depression era. Many of the men we had met at the Pine Street Inn were already waiting for us when we arrived. We set up a literature table with information about Food Not Bombs and the flyer I had produced about the policies of the Bank of Boston. We tied a few balloons to the mirrors and door handles of our van and set out the 60-quart pot of soup, paper bowls and a few loaves of bread.

The men from the inn gathered and made a line down the sidewalk towards Canal Street and South Station. A business man stopped to tell us he was shocked to see the line. “I have only seen soup lines in movies. I sure hope this doesn’t become a necessity.”

We shared the soup with not only the many homeless that came, but also business people who were walking pass. We also talked with a few stockholders who stopped to share their anger at the bank’s policies. Several of those from the inn suggested we do this every day.One of them

told us, “There isn’t any food available for us during the day. We get coffee and donuts before they kick us out and donuts and coffee when we return for the night, but there aren’t any food programs in Boston that provide cooked meals.”

The economic policies of the Reagan Administration had only just begun to wreak havoc on working people, and very few Americans were homeless.. By the end of the Reagan Administration the homeless population had grown from less than 100,000 mostly homeless vets to over 750,000 people, including many families.

That evening while cleaning up from our first soup line we decided to quit our jobs and dedicate our time to food recovery, grocery distribution, and the street theater of sharing vegan meals while conveying a radical message. Maybe we could slow Reagan’s economic policies of deep cuts in public housing, education, food, and social welfare, and the redirection of federal taxes towards the expansion of the military.

We started a daily routine of recovering produce, baked goods, and tofu donated by local shops, and delivering it to community rooms at public housing projects, shelters, and to others in need. Each evening Food Not Bombs volunteers would set up a literature table along with a table of vegan food at Harvard Square, the Park Street Station, and other public locations. Often people would drum and play other instruments, and at times we would organize puppet shows and other theatrical activities

during the evening meals.

Eight years later, after eight years of President Reagan’s bank-friendly policies, the Food Not Bombs theatrical soup line of March 26, 1981 had become a soup line of necessity.

The 1981 soup line outside the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston was just a theatrical memory of the Great Depression. For over two decades it’s been a necessity. I delivered produce to Occupy Boston outside that same bank in 2011. The capitalist political and economic system continues to produce the poverty, hunger, and suffering that is a natural outcome of a sociopathic system of institutionalized greed.

The eight of us were very optimistic that crisp March day in 1981 believing we could change the world. And yes, we accomplished much more than we could ever have imagined. At the same time, we could not have imagined just how much more we would need to do.